From 2005 to 2023, a father and a son discuss the riots! Some things will never change. Ladj Ly chose Montfermeil as the backdrop for his modern-day tragedy. A century earlier, Montfermeil was already the setting for Victor Hugo’s novel “Les Misérables“. In 1995, Mathieu Kassovitz depicted urban riots in the housing projects that followed a judicial blunder. After “Le thé au harem d’Archimède“, it was one of the first films to put a face to what the French call “les quartiers” – the marginalized neighborhoods. “Les Misérables” and many other films followed, echoing the same pattern: injustice, blunder, and riot.

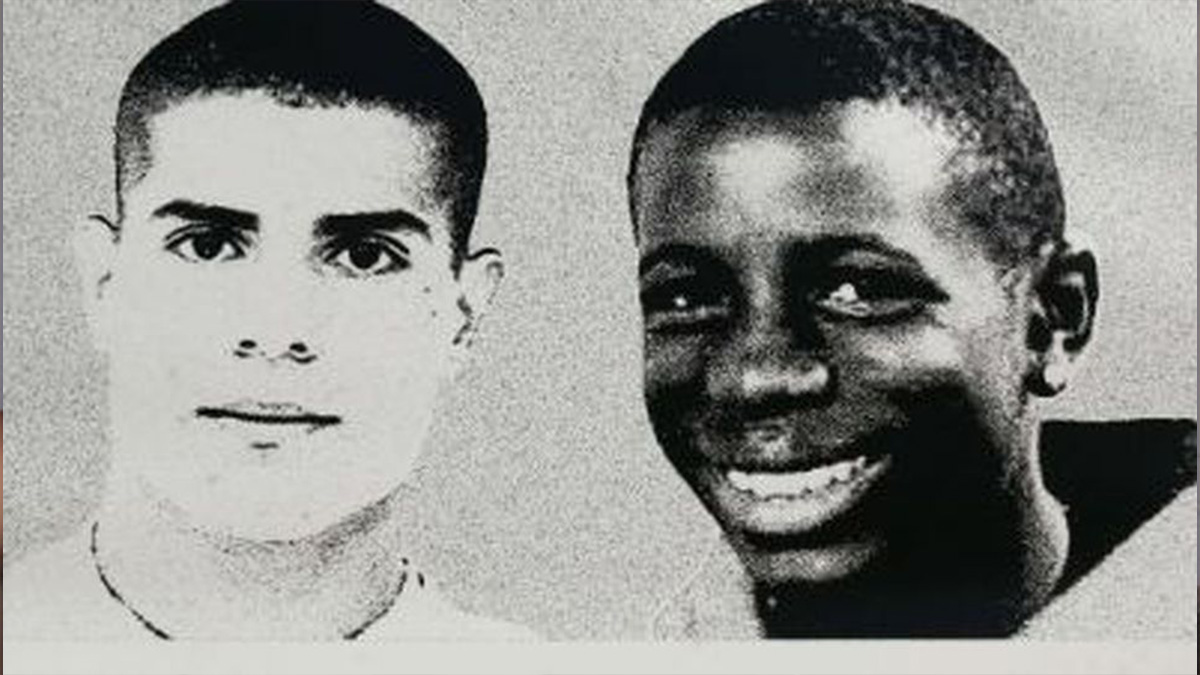

The newspaper Libération brought together a father and his son in a conversation about betrayed expectations. The father took part in the 2005 riots after the deaths of Zyed and Bouna, while his son participated in the 2023 riots. Libération sheds light on the faces of most of the rioters. They are not thugs, criminals, or gangsters; they are two men from different generations who have been driven to the streets by the force of injustice. The father recounts, “We are ordinary people who feel concerned about police madness. In such situations, anyone can quickly snap, even the kindest individuals. Acting out is not something planned. How can you expect some parents not to be overwhelmed?”

“Tyrants are only great because we kneel,” Étienne de La Boétie.

Two generations bear witness to the failure of urban policy!

The father looks at his son on the morning of the riots that shook France. The son gazes back, dazed, and reluctantly admits, “I was with them, but I did nothing.” The father then remembers the year 2005. Zyed and Bouna, two children, lost their lives after a police chase. The death of these young individuals, whose neighborhoods have still not healed, led to months of urban violence.

The father stood alongside the rioters, residing in Courneuve, when the tragedy occurred. He tells Libération, “I was heading home. There was noise, flashing lights, and smoke everywhere. I approached, and I can’t explain it, but I picked up stones and pieces of wood lying around and threw them towards the police. It wasn’t like today, with looting. We truly had rage.”

Having experienced humiliations by the police, he suggests, “I wasn’t even on the phone, and I had my seatbelt on. The officer knew it. I refused to sign the ticket. I shouted, I insulted him, and he laughed with his colleague. I felt helpless and alone. When I got home, I was in tears, so furious. I knew police checks, provocations, insults… I was familiar with all of that, but I had never experienced something like that before.”

In 2005, the riots changed nothing, neither the outcome of the case nor the government’s policy towards the neighborhoods. The recent outbreak of riots is the strongest evidence. Therefore, the father tries to teach his son a lessonthat transcends language barriers: “I swear to you, it’s pointless. Hurling stones, getting into confrontations, setting things on fire. You always lose,” the father continues, talkative. “I understand the rage, and I don’t have a magical solution, but you never win. I don’t regret throwing stones in 2005; I own up to it. But later on, I realized I would never do it again. Who gained anything from that episode?”

When asked about his son’s participation in the riots, he suggests, “I’m not the type to shout, and neither is my wife. When I was younger, I witnessed fathers beating their children, really going at them with big pieces of wood or electrical cords. It only drove them crazier. I simply told my son that it was dangerous. Even when you think you’re doing nothing, associating with those who set fires is being on the wrong side. The police won’t bother to differentiate, and it’s the same with projectiles. Since then, he doesn’t go out at night. He will do so again when the situation calms down.”

Behind these two witnesses lies the failure of the French society. To echo the words of a rapper who is not yet a singer, “If this were my final outcry, I would accuse France. It will pay for its repression when it loses its children.” Other authors from the 19th century “accused” France in different circumstances.