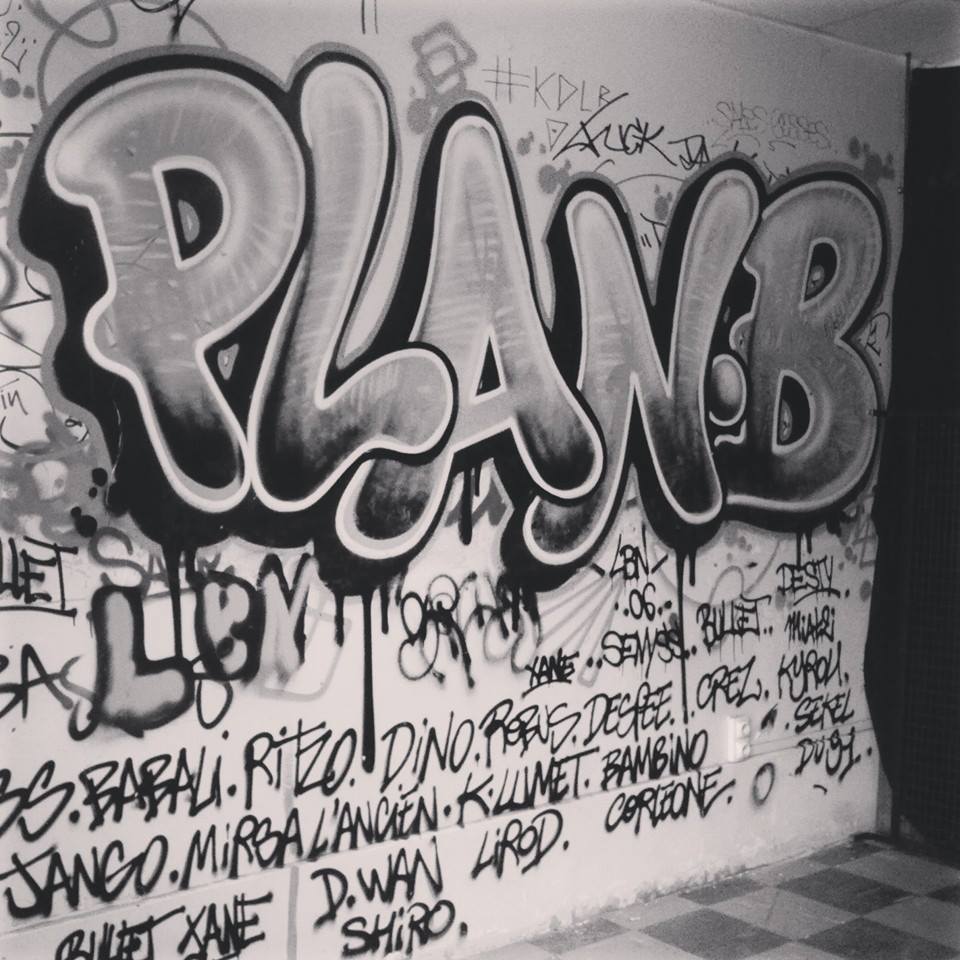

I spend my time with Srab and DJ Kefas, two very different characters. My intern, Alex, accompanies me almost everywhere. Srab invites us to the Plan B, an artistic squat that also provides shelter for people in real difficulties. Naive and very Parisian, I approach a guy and ask him if he likes being here. He answers yes but that he prefers Funk. A bit more innocent, I ask if he’s a rapper, and he coldly replies that no, he’s just going through a rough time at the moment. But this Plan B is the last bastion of the Hip Hop spirit, much like Srab. Money seized this music a long time ago. The vocal flights of Gims have nothing to do with the rap of the founding fathers. Too bad, Hip Hop succeeded, it became the popular soup of the “Les Misérables”. The common people need Rap to dream, to feed themselves. It’s the “Opium of the Neighborhoods”. You’ve been on social assistance for 5 years, no problem, because Maes releases “Les Derniers Salopards”. You’ll find a way to calm your anger in his somewhat clouded punchlines.

Before heading to the Plan B, Srab gives me a ride. He introduces me to Ursa Major’s latest mixtape, featuring some new faces like Gueule d’Ange. It’s clear to me that for Srab, Rap is no joke. He pops the “CD” into his car stereo, cranks up the volume on his car’s sound system, and shouts “Gueule d’Ange damn it,” “Gueule d’Ange damn it” every two seconds. And when I try to talk, he goes back to his discourse on the testimony of the silent minority, the lost art, the testaments betrayed by this new generation. But what can you do? It’s the first thing JR from GP told me when I started playing “the elder”:

“You, yes you, they bring you a contract in front of your eyes. They tell you that instead of making music for your friends, you’ll make music for everyone. That you’ll be rich, and you just have to accept an artistic direction. What are you going to do? Refuse and go back to the 94 to sell 100 e and rap for the hood?”

No one is incorruptible in this world… Well, upon closer thought, and especially seeing Srab nod his head to Gueule D’Ange, I think that maybe yes, Srab is the kind of guy who could throw a Major contract at your head and go back to his hood… Finally, we arrive at the Plan B. Everyone is completely wasted. There’s more beer than speakers, and we grill some sausages. We interview Babali Show, Alex my intern is great but still as clumsy. Bonhomie follows him everywhere, he’s got a Mr. Bean side to him. After 4 attempts, he turns on the camera. Babali Show just came out of a movie. No kidding?

Yes, in this Plan B with quite a few enthusiasts, we come across a certain Pascal Tessaud. The director, a working-class individual at heart, passionately advocates for his culture in both music and cinema. He’s one of the guardians of the temple, especially since his film “Brooklyn” was selected in New York and at the Acid Festival in Cannes. “Brooklyn” tells a story within the Rap scene. No guns, no mafia, even fewer flowing drugs; the director takes the bet of sincerity. And he finally receives the deserved recognition amidst the fantasists who exploit the history of the neighborhoods. We watch them for a while, though.

Pascal decided to make his film with real rappers from the 93. He specifically chose Babali Show and the formidable Despee Gonzales. Both men are present. But with Alex struggling to frame shots, Babali being stoned, and me panicking, it’s ultimately Srab who saves the interview. He exudes a “Strength & Respect” vibe, a “Respect & Honor” energy – he’s the “Lacrim” of independent Rap. I finish the video interview, and I start to think I might end up becoming the Raphael Mezrahi of Rap with all these mishaps. Nothing ever goes as planned. I look for Alexandre; he’s already munching on sausages while chatting about rap here and there. Alex comes from an affluent background, but he has no trouble integrating into this scene. The Hip Hop community appreciates his voluntarism and modesty. He’s found his place here. To make matters worse, Srab is looking for Gueule d’Ange, and I find myself having a quiet conversation with Shiro from Ursa Major. Here, nobody is really acting like gangsters or stars. If Paris were New York, the 93 would be the founding Bronx in the history of Hip Hop. Yes, it would be here. Srab invites me to have lunch at his mother-in-law’s place.

It’s quite an experience to find myself at his mother-in-law’s house. The veiled mother-in-law, far from the BFM TV fantasy, prepares a traditional North African dish for us. She’s very cheerful and friendly. His wife, a nurse by profession, struggles to contain Srab, who, even between his two daughters running in all directions as if we were already in the hell of marriage, keeps talking about Hip Hop at the table. The family respects his passion for rap… We know that without it, he’d have a hard time living. He pounds the table several times while his mother-in-law and wife struggle to follow his lyrical rants about Ursa Major. It’s as if he’s rapping at the table, freestyling, and then knocking something over. Meanwhile, his two daughters continue to circle the dining table. It’s incredible; I don’t understand anything anymore. He walks me back home with Gueule d’Ange’s solo playing, his Tupac of the day.

When I get back to my neighborhood, DJ Kefas calls me to say he’s coming to hang out at my friend’s place with Malfra. Okay! He arrives with Malfra and, more importantly, a new idea. DJ Kefas was involved in the rise of many rappers back in the day. His secret? He’s obsessed with mastering techniques, like dissecting the Facebook ad manager to the point where he could earn a like for 0.0000001 cent. After that, he boasts about it for hours with his trademark expression: “So, who’s the boss now?” But DJ Kefas is the opposite of Srab: “I’m here to make money.” He’s already given his passion to Rap; now he wants money. We have fun making prank calls for his radio show. And we call Srab. Srab doesn’t recognize him right away. The two guys genuinely get into an argument, both promising to unleash hellfire on each other. Then DJ Kefas tells me he has a client for me, “Le Champion,” a rapper from Toulouse.

Well, the guy is quite a character. He doesn’t really know how to rap, but hey, I’m new to communication, so okay. I get in touch with him. After 40 minutes of a Facebook conversation, I start to have doubts about his mental health. “Le Champion” is really not stable. He promises me a money order. He sends it to me the next morning. I show up at the Porte D’Orléans Post Office. After a somewhat racist remark, the guy at the counter tells me my money order doesn’t exist. I call “Le Champion” as I leave, and he tells me I’m a thief. I look it up on Google. The picture of the money order he sent me is the first image that comes up when you search for “money order.” I call him back; he apologizes and promises to send a payment via carrier pigeon the next day. I go back to bed, waiting for better days.